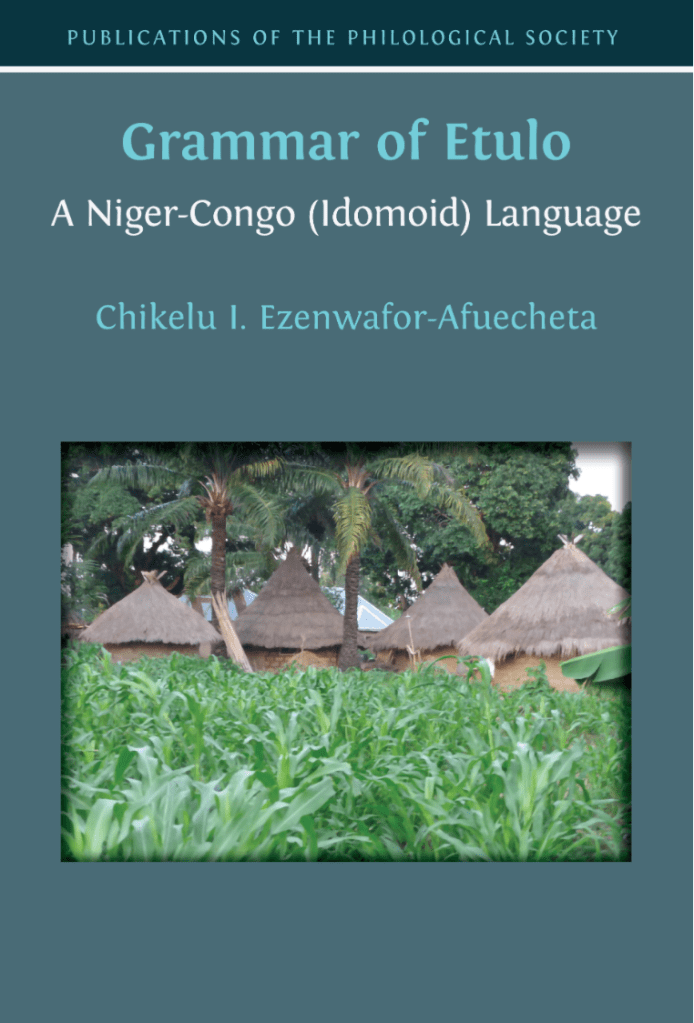

We are delighted that the first open-access monograph of the Publications of Philological Society was published last month by Open Book Publishers. The monograph, entitled Grammar of Etulo: a Niger-Congo (Idomoid) Language by Chikelu I. Ezenwafor-Afuecheta, is available to read online or to download in PDF format free of charge.

In this post, we had to chance to speak to Chikelu and ask her about her experience of researching and writing the grammar. Thanks very much to Chikelu for her thoughtful responses.

- How did you first come into contact with this language and what drew you to study it?

Nigeria is home to numerous minority languages, many of which face varying levels of endangerment; one of these is the Etulo language. I first encountered Etulo back in 2010, while doing a Master’s program in Linguistics. One of my classmates had spent her compulsory youth service year living among the Etulo community in Benue State. I was looking to focus my MA thesis on a minority language, and meeting her and through her being introduced to the Etulo community in Buruku Local Government Area, Benue State, greatly influenced my choice of Etulo. Moreover, Etulo fits a textbook case of a severely endangered language: it’s not taught in schools or used for instruction, it lacks a codified standard, and is only used in everyday home and marketplace conversations in Etulo-speaking areas, where it exists alongside stronger languages like Tiv.

- What kind of data did you work with when compiling this grammar? Can you talk us through the process of collecting this?

My research relied entirely on linguistic field data gathered through direct elicitation from native language consultants between 2014 and 2023. The Etulo speakers I worked with are trilingual, fluent in Etulo, Tiv, and partly English. Generally, most Etulo speakers in Benue State are bilingual, speaking both Etulo and Tiv, with Tiv being the dominant local language in the area.

To establish the phonemic inventory of Etulo, I made use of the Swadesh wordlist, Blench’s (2008) comparative wordlist, and the SIL Comparative African Wordlist (SILCAWL), which contains 1,700 lexical items. For morphological analysis, I employed Štekauer’s (2012) questionnaire on word formation processes. Additional syntactic data were obtained using questionnaires from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, including Klamer’s (2000) valence questionnaire, the relative clause questionnaire developed by members of the Bantu Psyn project (University of Berlin and Université Lyon, 2010), and Hengeveld’s (2009) questionnaire on complement clauses.

I also used picture-based tasks to elicit data on tense and aspect, as well as narrative and folktale materials to complement the dataset.

- How did you decide what to include/exclude, and the order of the chapters?

Before beginning the main phase of my research, I reviewed published grammars of both African and non-African languages to gain a foundational understanding of how grammatical descriptions are structured. Dixon’s Basic Linguistic Theory (Volumes 1–3) was especially useful in guiding the development of my initial set of fieldwork questionnaires.

Data collected during fieldwork later helped refine and narrow down which linguistic features were relevant for inclusion in the Etulo grammar. In certain cases, grammatical categories featured in the questionnaire such as gender or noun class distinctions were not attested in Etulo, and thus were excluded. Conversely, some features, like tone polarity, which were not initially part of the questionnaire, were incorporated into the grammar after being identified as salient in the data.

In essence, the structure of the Etulo grammar was initially influenced by existing grammatical prototypes of African languages and by Dixon’s theoretical framework, but was continuously adapted based on empirical evidence from Etulo. The chapters were organized from the smallest level of linguistic analysis (phonology) to the largest (syntax).

- Did you find any features of the language that you weren’t expecting, or that presented a descriptive challenge?

In the course of describing Etulo grammar, I encountered a few analytical challenges—two of which are particularly noteworthy.

The first challenge concerned the Etulo phoneme inventory, specifically the analysis and representation of certain vowel sequences such as [ie, ɪʊ, ɪɔ, io, ia, ɪa, uɛ, ue, ua]. The key question was whether these should be treated as glides (/j/, /w/), as diphthongs (single vowel units), or as non-identical vowel sequences that can each carry tone. Earlier work on Etulo by Armstrong (1974) interpreted these sequences as glides, thereby introducing additional phonemes like gy andky into the inventory.

However, this approach presents a problem: it unnecessarily expands the phoneme inventory, violating the principles of economy and pattern consistency, since these vowel sequences can occur after many consonants in Etulo ( ky, gy, fy, by, my, tsy, bw, fw, tsw, mw as in kye gya bwa fwa.) and as single vowel sounds. Moreover, analyzing them as glides overlooks the fact that the vowels in these sequences often exhibit tonal contrasts that remain distinct. Nor could they be treated as diphthongs, as each vowel in a pair can independently serve as a tone-bearing unit. Consequently, I opted to analyze them as non-identical vowel sequences capable of bearing either identical or contrasting tones.

The second challenge involved the internal structure of Etulo verbs. Many verbs in Etulo require a noun to co-occur with them as a meaning-specifier, a feature typical of several West African languages. The semantic bond between the verb root and its nominal complement is often so tight that native speakers perceive some verb-noun combinations as single lexical items. This perception may also be reinforced by phonological processes such as vowel elision and contraction, which are frequent in rapid speech. For instance, the verb ʃí áʃí ‘to sing’ is often realized as ʃáʃí after elision of the verb’s final vowel.

The main difficulty, therefore, was distinguishing the verb root from the noun complement. In cases where this distinction was unclear, I relied on syntactic tests specific to Etulo, such as constructions involving noun fronting and verb-root reduplication, to identify the true verb root.

- Why do you think language documentation is so important?

Language is far more than a marker of identity. It is an essential part of culture, the embodiment of a people’s values and knowledge, and the vehicle by which culture is communicated and handed down from one generation to the next. In an era when identities, languages and cultural traditions are vanishing, the task of preserving what remains becomes crucial: through documenting folktales, fading vocabularies, cultural rituals, proverbs, or grammars, we safeguard not just words but the depth of a civilization, the sense of self and community that once felt both sacred and enduring.

- If someone wanted to learn more about Etulo and other Niger-Congo languages, where would you direct them?

The Niger-Congo language family is a vast phylum made up of numerous subgroups, some of which are more developed than others. For example, the Igboid and Yoruboid groups, both spoken by millions in Nigeria are relatively better documented and developed, despite also facing endangerment. In contrast, the Idomoid subgroup, which includes minority languages such as Idoma, Yatye, Akweya, Akpa, Eloyi, Igede, Alago, and Etulo, remains far less developed.

While it is easy to find grammar books, online learning materials, and university programs dedicated to Igbo and Yoruba, the same cannot be said for Idomoid languages. Regarding Etulo specifically, its development has not yet reached the point where learners can readily access structured online or physical resources for language learning. However, the Nigerian Bible Translation Trust, in collaboration with some Etulo speakers, has developed an orthography proposal and translated parts of the New Testament into Etulo. There is also a historical account of the Etulo people written by Tabe (2007), along with a few other published studies available online.

Beyond publishing a grammar of Etulo, it is clear that the language requires comprehensive documentation of its cultural heritage. This realization has motivated my current collaboration with members of the Etulo community to develop a proposal aimed at recording Etulo folktales and proverbs, many of which are rapidly disappearing under the growing influence of Tiv, the dominant language and culture in Benue State, Nigeria.From my personal experience, the Etulo people were consistently warm and welcoming, and it was a genuine pleasure to collaborate with them in producing the grammar of the Etulo language. While this work is not without its imperfections, it nevertheless establishes a solid foundation for future teaching materials and further linguistic research on Etulo and other languages in the Idomoid languages subgroup.