written by Vasiliki Vita (SOAS University of London), recipient of a travel and fieldwork bursary from the Philological Society

1. Introduction

As a Micronesianist, I was not sure how my contribution at a conference about African Linguistics would be significant. However, when I was invited to work with Tom Jelpke and John Kyamanywa in Uganda, I thought this would be an excellent opportunity to share knowledge and learn more about Uganda and its languages. Thanks to a Philological Society bursary, I managed to travel to Uganda for 10 days in order not only to fulfill the goals of a British Institute in Eastern Africa Thematic Research Grant, but also attend the Languages Association of Eastern Africa 3rd Conference on “Empowering Communities through Language Research and African Linguistics for Sustainable Development”. In the title, I use wayfinding as defined by Iosefo, Harris & Holman Jones (2020: 23), “an embodied, practical, adaptive and relationally driven practice, … [that] calls on researchers to immerse themselves in journeys of discovery and transformation that value [Indigenous] cultural knowledges and acknowledge [their] blind spots”. In the case of this journey, the war[1] was not our piko[2]. It was the Boda Bodas, local motorcycle taxis, that carried us through this journey. I am also using the plural “we” because I will be talking about this journey as one that “cannot be viewed as belonging to any one person, and wayfinding is never done on one’s own” (Iosefo, Harris & Holman Jones 2020: 21).

2. LiVanuma and stories

LiVanuma is a language spoken in Bundibugyo, Western Uganda, near the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo. According to CCFU (2015), the BaVanuma ethnic group is estimated to have fewer than 25,000 people in Uganda, many of whom do not speak the language (Kyamanywa & Jelpke forthcoming). Building on their research, Kyamanywa and I embarked on a journey to document family histories, experiences, and languages. The aim is to compile a biographical (hi)storybook to tell the stories of BaVanuma people in Uganda in their own language (Jelpke, Kyamanywa & Vita 2023).

3. Wayfinding in Bundibugyo

To document these stories, we flexibly travelled on Boda Bodas from village to village to reach BaVanuma people who were willing to share their story (see Figure 1 for example). We must recognize the contribution of local coordinators for reaching out to various speakers and getting us in touch with them. Later, attending the conference, Wizlack-Makarevich (2023) referred to this kind of language documentation as the “helicopter method”, of going from place to place, gathering data, and relying on local intermediaries to help make the connections.

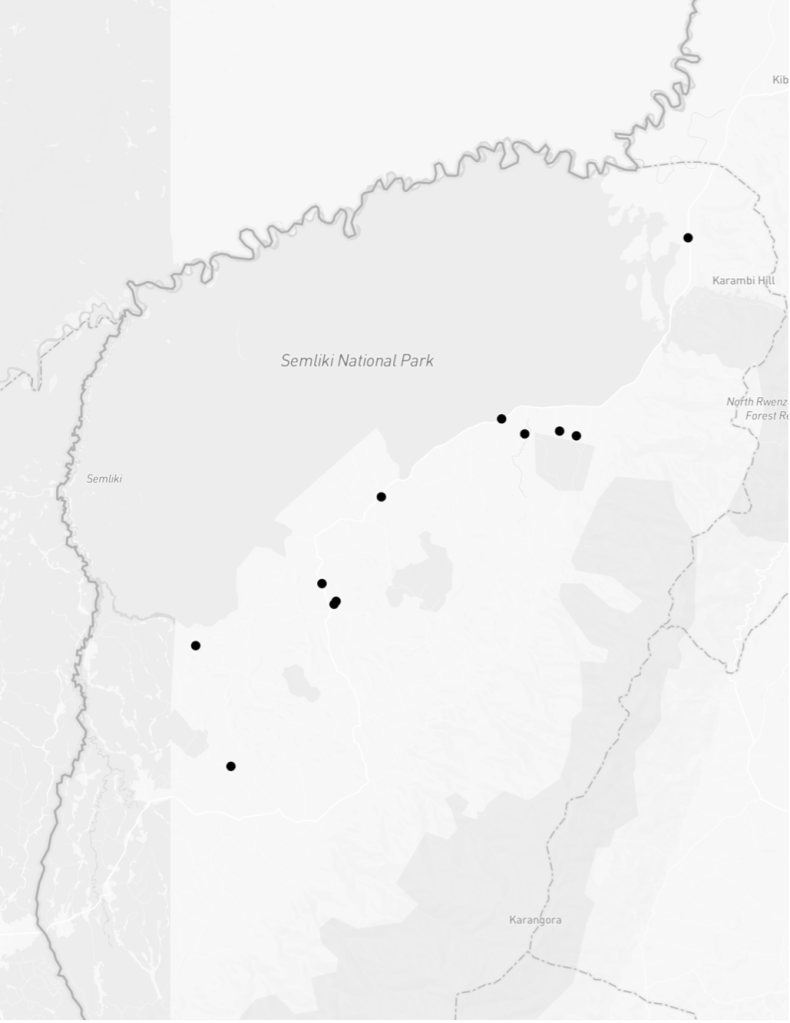

The piko here might physically be a different one, but it is still a war that allowed us “to stay in continual communication with the world around” us (Rogers 2020: 153), and “to move from stillness, bringing the island to [us] through ‘be-coming’” (Spiller 2016: 31). Like Pacific wayfinders we used our war as “the geographical centre of navigational orientation” (Eckstein & Schwarz 2019: 30) and removed “the lines on the map that segregate and compartmentalize” (Iosefo, Harris & Holman Jones 2020: 21) our world (see Figure 2 for a map of our journey with the black dots symbolizing the villages we visited).

The documentation process included making audio and video recordings of speakers narrating family stories, talking about their relatives, experiences living in Uganda and what the LiVanuma language means to them in terms of personal and community identity, as well as wellbeing. After narrating their story, speakers were encouraged to listen to their story and write it down (Figure 3). Participants in Kyamanywa and Jelpke (forthcoming)’s project had expressed an interest in writing the language.

4. Kampala and LAEA 3

The journey back to Kampala was a tiring one with us taking a different war this time and 10 hours to reach our destination. John and I talked about the mountains in the Bundibugyo District and reminisced about our journey through them. As Conquergood (2002: 146), Iosefo, Harris & Holman Jones (2020: 23) put it, our wayfinding was not just “moving and inhabiting”, but “a relational practice with the earth and sky”, “anchored in practice and circulated within a performance community”. After getting enough rest, we prepared for a full two days of conference talks learning about the work of colleagues in Africa.

In the first plenary talk, Nyaga (2023) focused on promoting mother tongue education and encouraged everyone to speak African languages at home. Kyamanywa and Jelpke’s talk then started, where they presented the preliminary results on documenting the LiVanuma sociolinguistic landscape. It was interesting to see people’s reactions in the audience, with many Ugandan researchers noting that they had never heard of the BaVanuma people and their language before. As wayfinders, we share stories in true embedded and embodied fashion through relationship and collective engagement with multiple ways of knowing (Gounder 2015).

What I found most interesting, was the plenary on the second day by Alena Witzlac-Makarevich. Wizlack-Makarevich (2023) encouraged for the multi-modal documentation of African languages, which comparatively to other places around the world is lagging (Lüpke 2019). She talked about the importance of data governance and recognizing the value of corpora in language maintenance and promotion, especially for endangered languages.

My talk was also on the second day. Listening to other researchers, I realized once again, that boundaries are fluid, and knowledge is to be shared regardless of where it was acquired. “Hyper-collaboration” in the sense used in Di Carlo et al. (2022) and Vita, Nestor & Marino (2023) focuses on the value of the network that can be activated at any time for activities that benefit the group most impacted. Language-related initiatives and activities presented at the conference also showcase the fact that they all start with documenting and reaching out to tradition but are borderless and rooted in the desire for belonging (see for example Okurut, Kiguli & Tibasiima (2023) discussing the music of an expatriate Ugandan artist).

5. Conclusion

Our wayfinding in Uganda was not limited by borders and lines on the map. It was active, intimate, hands-on, and participatory, like the ‘traditional’ knowledges of Pasifika people (Iosefo, Harris & Holman Jones 2020). Attending the 3rd Conference of the Languages Association of Eastern Africa was an invaluable experience not only for sharing our work, whether that is with John and Tom, the Young Historians of Sonsorol or the virALLanguages initiative, but also discovering the work of African colleagues and further work on the documentation and maintenance of linguistic diversity. My wayfinding continues and I am thankful for all the individuals who consider me worthy to invite to the journey.

Endnotes

[1] Sonsorolese word for “canoe” which is nowadays used to describe any means of transport, including airplane and car

[2] Hawaiian word for “navel”.

[3] For a more detailed labeled map, visit: https://goo.gl/maps/4NGnwXtPt6MLzoBj8.

References

Conquergood, Dwight. 2002. Performance Studies: Interventions and Radical Research. TDR/The Drama Review 46(2). 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1162/105420402320980550.

Di Carlo, Pierpaolo, Leonore Lukschy, Sydney Rey & Vasiliki Vita. 2022. Documentary linguists and risk communication: views from the virALLanguages project experience. Linguistics Vanguard. De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2021-0021.

Eckstein, Lars & Anja Schwarz. 2019. The Making of Tupaia’s Map: A Story of the Extent and Mastery of Polynesian Navigation, Competing Systems of Wayfinding on James Cook’s Endeavour , and the Invention of an Ingenious Cartographic System. The Journal of Pacific History 54(1). 1–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2018.1512369.

Gounder, Farzana (ed.). 2015. Narrative and Identity Construction in the Pacific Islands (Studies in Narrative). Vol. 21. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.21.

Iosefo, Fetaui, Anne Harris & Stacy Holman Jones. 2020. Wayfinding as Pasifika, indigenous and critical autoethnographic knowledge. In Wayfinding and Critical Autoethnography. Routledge.

Jelpke, Tom, John Kyamanywa & Vasiliki Vita. 2023. Cultural-linguistic priorities of a minority community: folk history, language documentation, and orthography development with the BaVanuma people of Bundibugyo, Western Uganda. British Institute of Eastern Africa Annual Thematic Research Grants 2023-2024.

Kyamanywa, John & Tom Jelpke. forthcoming. LiVanuma linguistic vitality: A sociolinguistic documentary project.

Lüpke, Friederike. 2019. Language Endangerment and Language Documentation in Africa. In H. Ekkehard Wolff (ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of African Linguistics, 468–490. 1st edn. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108283991.015.

Nyaga, Susan. 2023. Comparative issues in mother tongue advocacy in Africa: can negative attitudes towards African languages be changed? In The Third Conference of the Language Association of Eastern Africa. Kampala, Uganda.

Okurut, Lazarus, Susan Kiguli & Isaac Tibasiima. 2023. Place and Belonging in the songs of Madoxx Ssemanda Ssematimba. In The Third Conference of the Language Association of Eastern Africa. Kampala, Uganda.

Rogers, Christine. 2020. Almost always clouds: Stitching a map of belonging. In Wayfinding and Critical Autoethnography. Routledge.

Spiller, Michelle. 2016. Calling the Island to You: Becoming a Wayfinder Leader. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/32638. (6 September, 2023).

Vita, Vasiliki, Daphne Nestor & Lincy Marino. 2023. Experiences from documenting Ramari Dongosaro in a multilingual context. In. Online.

Wizlack-Makarevich, Alena. 2023. Creating and utilizing corpora for language description and development: lessons learned from three projects across the African continent. In The Third Conference of the Language Association of Eastern Africa. Kampala, Uganda.

2015. The Cultural Rights of Ethnic Minorities in Uganda – a call for action. Kampala: Cross Cultural Foundation of Uganda. http://crossculturalfoundation.or.ug/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/The-Cultural-Rights-of-Ethnic-Minorities-in-Uganda-A-call-for-action-@CCFU.pdf.

Interesting read 💯✔️

LikeLike