written by William Thurlwell (University of Oxford), recipient of a travel and fieldwork bursary from the Philological Society.

With the generous support of the PhilSoc Travel and Fieldwork Bursary, I had the opportunity to attend the 30th Germanic Linguistics Annual Conference (GLAC) at Indiana University, Bloomington, IN in April 2024.

The conference is amongst the best attended and most prestigious in the annual calendar for Germanic linguists. Having previously attended the 28thand 29th GLACs in Athens, GA, and Banff, AB, I knew how enriching and engaging it can be to hear about the work undertaken by others in the field and to receive feedback about my own research. This year was no different: my experience at 2024’s GLAC, on both a professional and personal level, was extremely rewarding.

I presented two papers at this year’s conference.

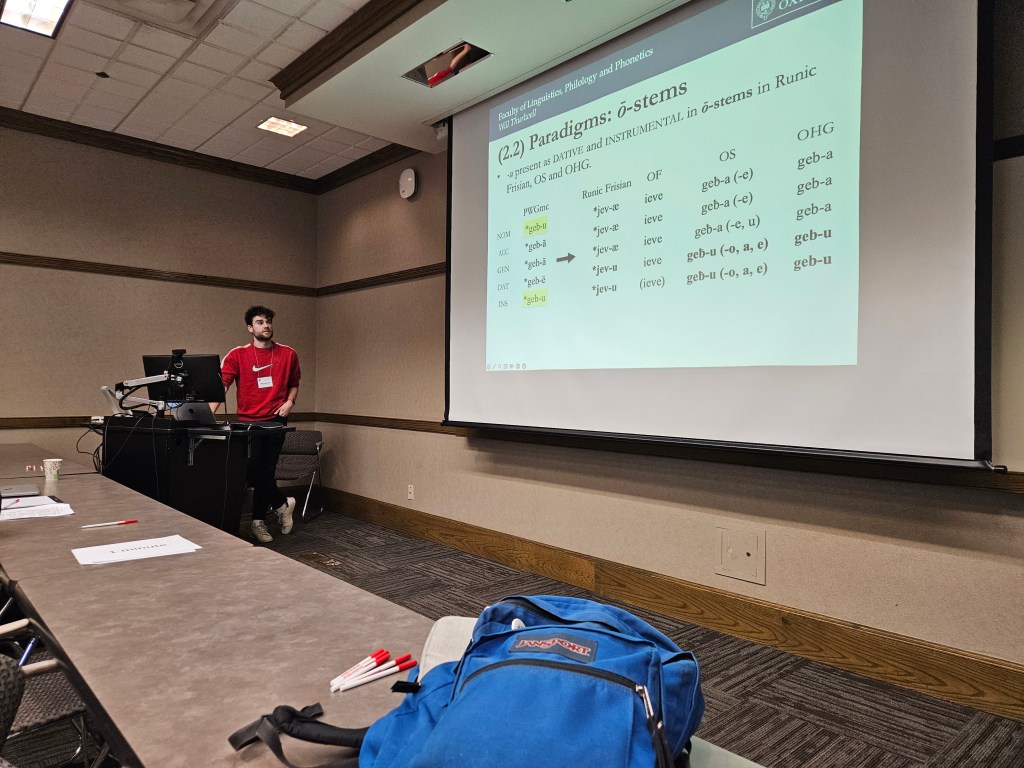

The first paper pertained to a philological aspect of my DPhil research, titled ‘Remnant Case Forms and Patterns of Syncretism in Early West Germanic’. In this paper, I examine the form and distribution minor morphological elements (-i and -u suffixes) which are used to convey remnant instrumental and locative functions in the a/ō-stem nouns of certain old West Germanic (WGmc) languages. Early Old English (OE) generalises its locative and instrumental functions under its ‘instrumental’ -i suffix (which later reduces to -e, the formally autonomous morpheme found in the strong inflection of masculine and neuter adjectives in later OE). By contrast, the continental WGmc languages (i.e. Old High German, Old Saxon, and Runic Frisian) generalise instrumental functions under the suffix -u, although some locative functions survive in a small number of tokens with an -i suffix. I propose that the divergent generalisations of the functions of the different instrumental morphemes are what motivate the dichotomy in the patterns of syncretism in the feminine ō-stems of continental WGmc and OE respectively.

The bridging factor between the instrumental case and the ō-stem paradigms is the -u morpheme. In Proto-WGmc, the nominative and instrumental are reconstructed as being syncretic in the feminine ō-stems under the suffix *-u (< Proto-Gmc *-ō):

Table 1. Development of ō-stems from Proto Germanic to Proto West Germanic.

| Proto-Gmc | Proto-WGmc | |

| nom | *geb-ō | *geb-u |

| acc | *geb-ǭ | *geb-ā |

| gen | *geb-ōz | *geb-ā |

| dat | *geb-ōi | *geb-ē |

| ins | *geb-ō | *geb-u |

There was a divergence in the salience of the -u morpheme across WGmc, since the historical -u is maintained as a marker for different cases in different parts of WGmc. OE favours the nominative function (at least in light-stemmed nouns) and continental WGmc favours the instrumental function. This can be seen in how the instrumental form was replaced in OE with -i, but not in continental WGmc, where the prominence of the -u morpheme persists and even proliferates, since the dative also merges under this ending.

Table 2. Paradigms of light-stemmed ō-stems in the West Germanic languages.

| Old English | Continental WGmc | ||||

| Pre-OE | Early WS | Late WS | Runic Frisian | OS | OHG |

| *geƀ-u | ġief-u | gif-u | *jev-æ | geƀ-a (-e) | geb-a |

| *geƀ-ǣ | ġief-ǣ | gif-e | *jev-æ | geƀ-a (-e) | geb-a |

| *geƀ-ǣ | ġief-ǣ | gif-e | *jev-æ | geƀ-a (-e, u) | geb-a |

| *geƀ-ǣ | ġief-ǣ | gif-e | *jev-u | geƀ-u (-o, a, e) | geb-u |

| *? | (ċæstr-i†) | gif-e | *jev-u | geƀ-u† | geb-u |

All of WGmc was subject to the apocope of high vowels after heavy stems (Fulk 2018: 82-3), which would have led to the retention of *-u in light-stemmed ō-stems only. This suffix only survives in the nominative in OE, but would have also been expected to survive as the light-stemmed instrumental, based on reconstructions, but there is no evidence that an instrumental *geƀ-u form survives (hence the *? in the cell in the above table).Ringe and Taylor (2014) propose that OE generalises an instrumental -i in this cell from the interrogative pronoun, whereas continental WGmc clearly maintains the inherited -u.

The generalisation of -i and replacement of -u in OE suggests that the salience of -u—at the time when it would have likely still been a syncretic morpheme in pre-OE—was analysed as nominative over instrumental. In continental WGmc, the converse was true: -u was lost as a nominative marker (and the nominative becomes syncretic under the accusative and the genitive form), but spreads as the instrumental and dative marker. This demonstrates how changes to the instrumental case in these two separate subgroups of WGmc sit at the heart of the developments in the syncretism patterns of the feminine ō-stems. The divergent salience of the historically syncretic -u morpheme is the primary motivator for why the ō-stems syncretise differently in different parts of WGmc.

The second paper I presented was a joint submission with my supervisor, Howard Jones, and recent Oxford DPhil student, Luise Morawetz, to present our progress about the book we are writing together under contract with Oxford University Press: The Oxford Guide to Old High German and Old Saxon. The purpose of the talk was to show what we have done so far, explain the rationale for the grammar and reader sections of the book, and to get feedback from peers in the field to ensure that the remainder of the project will best fit the needs of our intended audience: students and researchers of Old High German (OHG) and Old Saxon (OS).

I was very pleased with the feedback and questions I received to both of my talks. I received constructive suggestions about how to refine the approach to my personal research. Several fellow students and scholars offered motivating words about the book project and made useful suggestions as to how we might make the OHG/OS volume maximally useful both to those new to old Germanic languages and those who already have considerable experience with them.

Connecting with colleagues both old and new, having the chance to discuss new research ideas, and getting informal career advice was invaluable for me as I conclude my DPhil and plan the next steps in my academic journey. After three days of busy conferencing, I also took some time to explore parts of the Midwest and beyond, enjoying the rich cultural offerings of Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Illinois: I saw grand natural wonders, such as Mammoth Cave, the bustling metropoles of Indianapolis, Nashville, and Chicago, and the downright weird and wonderful, such as the World’s Largest Rocking Chair in Casey, IL. A personal highlight was being able to take my newfound hobby of running to American pastures, taking first place at the Cornerstone Lakes parkrun, a timed 5k which takes place on a weekly basis in the outskirts of Chicago.

Being able to attend conferences during my time as a DPhil student has been nothing short of formative in developing my research methodology and—pardon the pun—‘instrumental’ in furthering my academic confidence. Most importantly, I have forged new professional relationships and personal friendships across disciplines and continental boundaries. I would like to thank the Society again for their incredibly generous support in facilitating my attendance at GLAC in 2024.

References

Braune, Wilhelm & Heidermanns, Frank, 2023. Althochdeutsche Grammatik I, Berlin: De Gruyter.

Fulk, R. D., 2018. A Comparative Grammar of the Early Germanic Languages, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Gallée, Johan Hendrik, Lochner, Johannes & Tiefenbach, Heinrich, 1993. Altsächsische Grammatik, Tübingen: M. Niemeyer.

Goering, Nelson, 2023. Prosody in Medieval English and Norse, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ringe, Don, 2017. From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ringe, Donald A. & Taylor, Ann A., 2014. The Development of Old English, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Versloot, Arjen 2016a. ‘The Development of Old Frisian Unstressed –U in the Ns of Feminine Ō-Stems’. In: Bannink, A. & Honselaar, W. (eds.) From Variation to Iconicity: Festschrift for Olga Fischer on the Occasion of Her 65th Birthday, Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Pegasus.

Versloot, Arjen 2016b. ‘Unstressed Vowels in Runic Frisian. The History of Frisian in the Light of the Germanic ‘Auslautgesetze’’, Us Wurk, 65, 1-39.